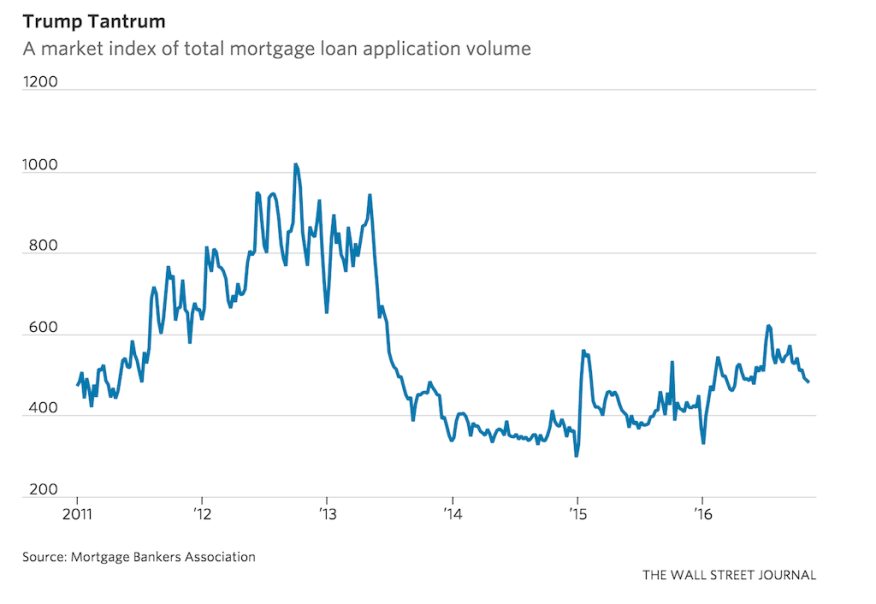

Historically dirt-cheap rates may be living on borrowed time.

A short note today, as I’m in Chicago, participating in our 13th Annual AHF Live! affordable housing event today and tomorrow.

Remember, interest rates–specifically as they bear on home mortgage rates and their impact on monthly payments for home buyers–were going to go up, sooner or later.

They rise, we’re told, for three principle reasons, normally. One is monetary policy, and the Fed is a veritable fishbowl of intent to track upwards with its borrowing rates. Two, is growth-fueled demand for borrowed money, which we like to see–as jobs, wages, and household expansion lead to people taking on debt against future earnings. Three, is inflation, which devalues money, and leads to lenders protecting themselves from risk of their funds shrinking in value by lending for shorter terms and higher rates.

However, there’s a fourth interest rate driver that also impacts interest rates, and it’s the one that’s cropped up as a stress-test to the housing recovery’s incipient expansion into the lower-priced, entry-level, and entry-level plus home offering.

Volatility.

So, let’s review. Higher than dirt-cheap rates have been expected. Their impact was and still is largely a guess for economists and analysts.

Here, Calculated Risk’s Bill McBride outlines the various and sundry ways “The Cupboard Is Full,” adding up economic data points on the latest retail spending, higher wages, demographics-fueled increase in working-age population, and housing demographics playing out pent-up demand. McBride writes:

“What could possibly go wrong?”

That there should be a period of intensified volatility amid rampant speculation about 1) what the President-elect intends to do, 2) what he will actually do, and 3) what meaning or impact those action items will have … is natural.

Fact is, though, we’re going to get a quick taste–like it or not–of how higher borrowing costs may affect would-be buyers.

Will they speed up their purchase process now, believing that rates are on a more permanent path upward? Or, will they tap the breaks, wait for the volatility to calm down and expect that rates will come back down?

That’s the question.

And we like McBride’s parting thought, too.

What could possibly go wrong?